Janez Bleiweis was born into a relatively wealthy Slovenian-speaking family in 1808. He was a veterinarian by profession, but he was also a man of the enlightenment – and determined to promote a distinct Slovenian cultural identity.

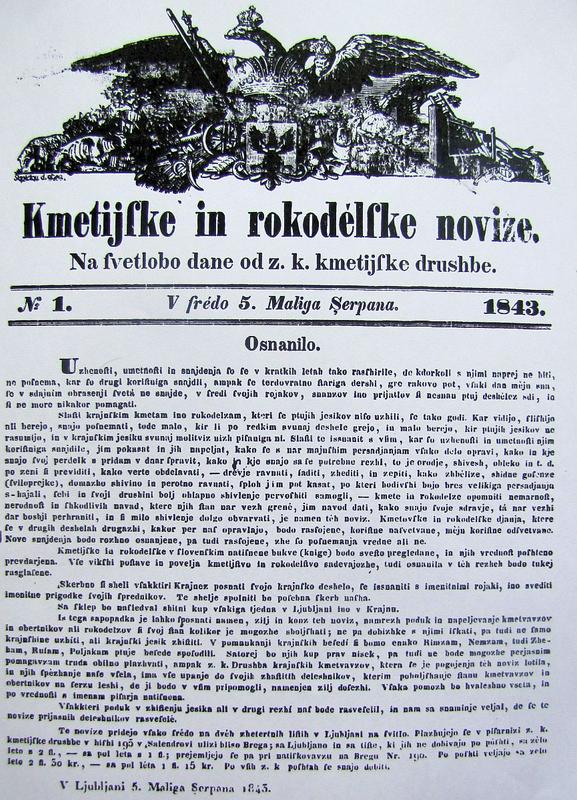

In 1843, he founded Farmers' and Craftsmen's News, a weekly newspaper. The publication, one of the first in the Slovenian language, was intended to provide practical advice to ordinary people, but it soon widened its scope to become Slovenia’s first truly influential newspaper. In addition to covering important events in the Slovenian Lands, it also emerged as an influential platform for leading figures of Slovenian political and cultural life -- people such as Janez Trdina and Simon Jenko. It established itself as a powerful counterpart to Ljubljana’s leading German-language newspaper, Laibacher Zeitung.

Various poets and writers contributed to the newspaper, but the Farmers' and Craftsmen's News also shaped the Slovenian language in a different way. For much of the 19th century, Slovenian had no standardized system for writing its special sounds. Instead, various modifications of the Latin script were used by different authors. Bleiweis’s publication helped to resolve the uncertainty by adopting the Czech-based alphabet devised by the Croatian linguist Ljudevit Gaj. Thanks in large part to the newspaper, Slovenian finally became a truly standardized language.

The News was also the first publication to print details of the “United Slovenia” program, which called for the creation of an autonomous Slovenian province within Austria-Hungry. Meanwhile, France Prešeren’s patriotic poem The Toast, which would later become Slovenia’s national anthem, first saw the light of day on its pages. Despite its national orientation, the News was never insular; it published translated poetry and prose by foreign authors, including the works of Lord Byron.

Not everybody agreed with the newspaper’s editorial policies. Even Prešeren was strongly critical of some of its language policies. And over the years, the conservative publication – strongly loyal to the Austrian Emperor and the Catholic Church -- began to lose ground to new, daily newspapers in the Slovenian language. It folded in 1903, more than two decades after the death of its founder.

However, it left behind and important legacy. Not only did it fully standardize the Slovenian language, but it also helped to give the onetime peasant tongue a status equal to German in the mass media.