The war ended on November 1918, but a lot of people returned many years later.

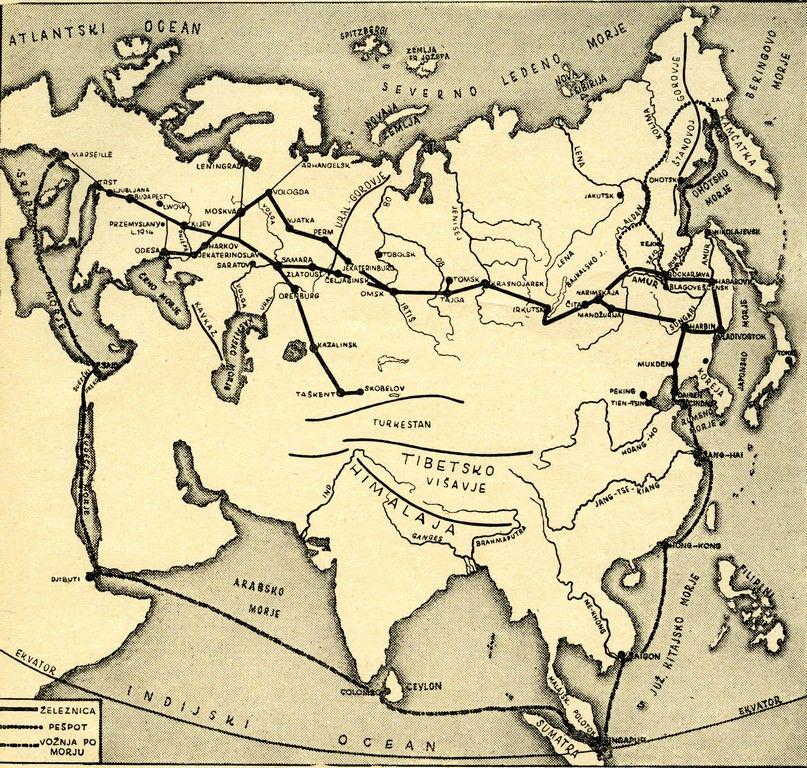

Martin Muc escaped from Russian prison camp by the end of 1917, and travelled through Siberia to Chelyabinsk, Omsk and Tomsk. Being resourceful, and lucky, he managed to survive the tragic Russian civil war. In Vladivostok he failed to embark on the boat due to a huge number of former Austro-Hungarian soldiers having the same wish – to return home. Therefore Martin Muc embarked on an adventurous trail towards "the golden fields" along the rivers of the remote Kamchatka. Later he escaped to Shanghai, where he finally managed to board a ship and return to Europe through Hong Kong, Saigon, Singapore, Colombo, the Suez channel, and Port Said. In Marseille he finally managed to obtain the necessary documents and to return home. In February 1927 he returned to Ljubljana, dressed in a shabby suit and a meagre suitcase, and from there to his native Metlika – where nobody expected his return any more.

Josip Košir was also sent to the Eastern front as a member of the 27th Home Guard infantry regiment. After a long captivity in July 1920 he managed to board the train in Tomsk, Siberia, and travelled through Moscow towards west, to the coast of the Baltic Sea. In Germany he embarked a steamer and returned home to Upper Carniola, travelling through Berlin, Bavaria, and finally Maribor.

Seven-year-old Marija Koršič had to leave her native village Pevma near Gorica, as the village was in the path of the front line. The fate took the refugee into a village near Kromeriž. Her story speaks of schools for refugees and teachers, and the influence they had on her future as a teacher. She returned home through the refugee camp at Strnišče near Ptuj, and came back to her native village Pevma only in 1920, where they erected a shack in the courtyard next to their ruined home.

Anton Grahek from Lokve near Črnomelj experienced battlefields from Galicia to Tyrol. He lived through the Bovec basin breakthrough, and the retreat of the Italian army through Tilment. As a soldier of the 22nd march battalion of the 17th infantry regiment he was assigned to the 3rd regiment of Tyrolean sharp shooters, and on November 3, 1918, instead of going home he was sent, together with a number of Austro-Hungarian soldiers, to a long captivity in Italy. After escaping from the prisoner camp, he came home in 1920, and the war was finally over for him as well.

Slovenian Odysseus

Nine more stories about returning home are described in the miscellany for the exhibition. Both the exhibition and the miscellany present a lot more cases of people returning home from the wars which raged in the 19th and 20th. 19 institutions from all parts of Slovenia participated in this project based on the universal antique theme described in the epic about Odysseus, the mythological hero who after twenty years returns to his native Itaka from Trojan wars, disguised as a beggar.

The exhibition will remain open until September 1, 2016.

Marko Štepec; translated by G. K.