“Climbers are aware that in addition to knowledge and skills, we are also very lucky that the mountain allowed us to reach its peak and even more lucky to descend from it safely.”

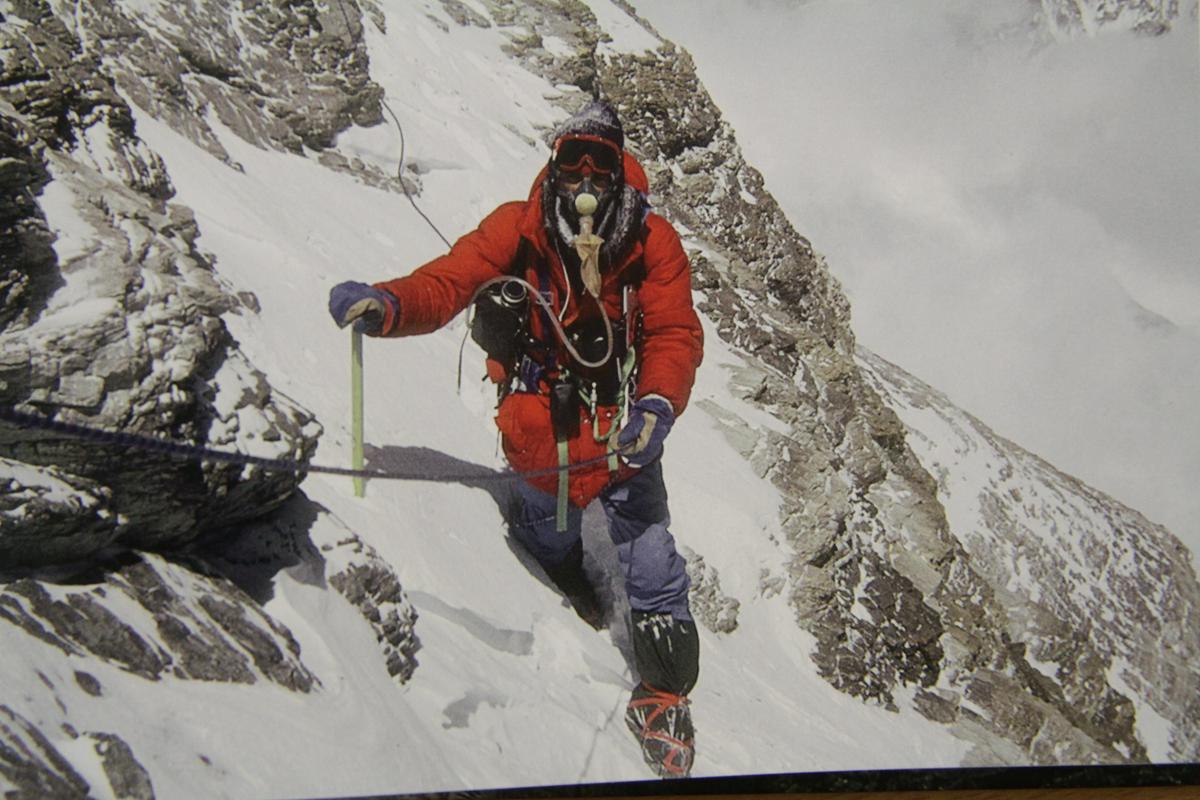

Viki Grošelj ventured to the Himalayas for the first time at the age of 23, and he is the Slovenian who has conquered the most mountains in the world. With no experience and plenty of good luck, he climbed the 8,463-metre high Makalu at the first attempt. Of the fourteen eight-thousand-metre mountains in the world, he has climbed ten, including the highest peaks on every continent.

How do you experience the Himalayas today?

The foothills of the Himalayas are much more accessible than in the past. The infrastructure has progressed in all aspects. There are more roads, airports and aircraft which can take you close to the mountain. The fact is that, in spite of the modern equipment and development of alpinism, one must still climb to the peak. The success of a Himalayan climber is based on strength, persistence and experience and these can also be nurtured in more mature years.

How much fear is still present when you climb in the Himalayas?

Just the right amount. I consider fear a positive quality because it protects you. To find an optimum limit or an optimum degree of fear is a particular skill. I can say for myself that I have been quite successful in achieving that after everything I’ve been through. At the time when I was obsessed with the Himalayas, I was completely focused on eight thousand-metre mountains, and now I have time to admire the beauty of Nepal. I would like to walk across it from east to west and write a book about it.

In the introduction to your latest book, Giants of the Himalayas, you write that you dedicated it to Slovenian climbers who died in the Himalayas and to three foreign climbers who died during expeditions you joined. The total death rate of 24 is high. How did you cope with these tragedies?

With more and more difficulty. Seven climbers have died on expeditions in which I participated. The first death was a terrible shock. It is difficult to understand that in such a beautiful place such a cruel interruption of dreams and life happens. I think too many Slovenians have died in the Himalayas. In spite all its beauty, top Himalayan climbing has only one bad side and that is danger. A small percentage of objective danger awaits you on the rock face which can’t be influenced regardless of your experience - falling rocks and ice, avalanches; everything else except these can be predicted. Nevertheless, climbing for me is the most beautiful activity in the world. Nejc Zaplotnik, also a climber, said to me that if anything happened to him he would like to stay in the Himalayas and, unfortunately, he did.

Who are the giants of the Himalayas to which you dedicated the book with the same title?

The giants are the fourteen highest peaks in the world higher than eight thousand metres. These are the main characters to which I added the most outstanding stories of foreign and Slovenian climbers who wished to climb them. All climbers have great respect for the giants.

In a way, Slovenians are the ambassadors of alpinism and positive values in Nepal.

That’s true. We give work to the locals, and also free medical services, and we promote them to other tourists. In 1979, we established a school for mountain guides where we taught the local people climbing skills. The head of the project was Aleš Kunaver. The number of casualties among the sherpas was simply too high because they lacked mountaineering skills. So we decided to educate them. Now, the Nepalese run these courses themselves. As a climber, you need many other skills. You have to be diplomatic and organise things. Language skills are also important, and also logistics, a sense of teamwork and finally, cooking skills.

Is climbing also about self-confidence?

Certainly. Climbing has definitely helped me in everyday things. The feeling that I can achieve good results somewhere gave me a lot of self-esteem. Foreign landscapes move me also because of the constant exploration of my own limits. I’m faced with universal values which rule the world. It’s about sympathy for people, for the world. I have learned a lot from the local people, particularly patience and gratitude; travelling has been at least one additional university for me. In addition to sport, I’m also interested in people, and I ask myself: how far can human kindness and also madness go? I have fewer and fewer answers.

What comes after 8,000 metres?

Perhaps peaks on the Moon. They are fifteen thousand metres high. Perhaps I will live until the tickets are cheaper. As excellent climbers, Slovenians will certainly be among the first there. To have a goal is the most important thing - to try to go beyond the possible, to explore something new. Commercial expeditions also require a lot of effort - they aren’t easy. But it’s not the same if you tackle the mountain alone or with a small team. There are plenty of challenges. That’s real passion. There are many possibilities even for more difficult climbing routes. It’s good to dream the impossible in order to achieve the possible.

In 2000, the legendary Reinhold Messner stated that it was the Slovenian climbers who took a decisive step in developing modern Himalayan climbing.

The first complete Slovenian success was achieved with the ascent of Annapurna, which is close to the magic limit of 8,000 metres. The main connection with the climbing superpowers was made in 1975 with the ascent of Makalu. For objective reasons, such as the lack of Himalayan experience and other priorities at the end of the Second World War, we missed the pioneering days of the first ascents of the Himalayan giants, and then, as Aleš Kunaver put it, caught that last train by overtaking it. We were very successful. In the 1980s, the Alpine style of climbing was established. The pioneer was Stane Belak, followed by Silvo Karo, Janez Jeglič, Andrej Štremfelj, Marko Prezelj, Tomaž Humar, Pavle Kozjek and Iztok Tomazin. Their followers were Rok Blagus and Luka Lindič and the recent winners of the Golden Ice Axe, Luka Stražar and Nejc Marčič. These are names which I hope will be at the top of world Himalayan climbing.

Let’s end with your beginning in the fifth grade of primary school.

Yes, I came across climbing by coincidence. I read a lot of mountaineering literature and that drew me in. I wanted to see the Himalayas at least once with my own eyes. So far, I’ve seen them more that forty times, but I’m always as stunned as I was the first time. I am grateful that my life has led me to where I can enjoy and learn more about life.

Vesna Žarkovič, SINFO

“Climbers are aware that in addition to knowledge and skills, we are also very lucky that the mountain allowed us to reach its peak and even more lucky to descend from it safely.”