In 1807, librarians at the Bavarian State Library made a startling discovery. They were examining a bound manuscript written in Latin, which they had recently received from the Bavarian town of Freising, when they discovered four leaves of parchment written in another language. They had stumbled upon the oldest written document in the Slavic dialect that would ultimately become the Slovenian language.

The text of the manuscripts is liturgical. Even though formal church services at the time were conducted in Latin, several related ceremonies – repentance sermons, for instance – were carried on in local languages. In Carinthia’s Möll River Valley, that language was Slovenian – or at least an early form of what we know as Slovenian. It’s believed that they were created around 1000 A.D., but were based on 9th century texts.

This was before Slavic languages began to diverge substantially, and the dialect used in the manuscripts resembles many present-day Slavic languages. In fact, several Slovak scholars once claimed that the dialect was in fact proto-Slavic until more comprehensive analysis disproved their theory. Certain characteristic linguistic features clearly indicate that the manuscripts were a very early form of the Slovenian language.

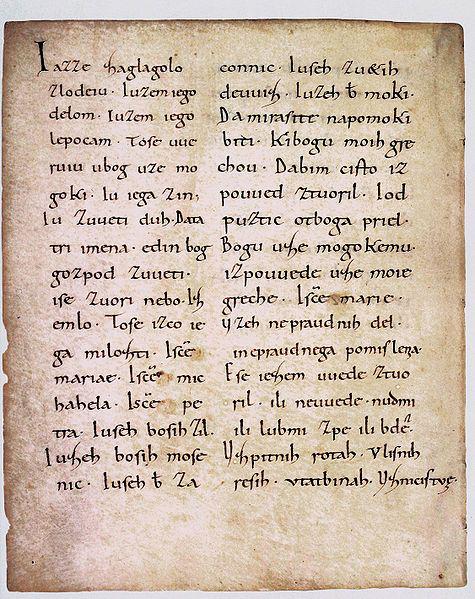

What makes the Fresing Manuscripts most special, however, is their script. They were written in Carolingian miniscule. While that type of Latin script was common in Western Europe at the time, the Freising Manuscripts are the oldest preserved Slavic documents to have been written in a Latin script. (Older Slavic manuscripts use Cyrillic and Glagolitic script.) The manuscripts mark the very beginning of Slavic writing in Europe’s dominant script.

Almost since their discovery, the Freising Manuscripts have captured the attention of Slovenian linguists, who used them to reconstruct the historical development of the language. They were reprinted between the two world wars, and in 2004, the originals were exhibited in Slovenia. The tour was the first time the manuscripts came to Slovenia, and the event received considerable media attention.

Today, the manuscripts are available online. Their host website, maintained by the National and University Library in Ljubljana, even enables users to listen to an audio reconstruction of the manuscripts. Scholars, students, and the curious can now travel centuries back in time to the very dawn of the Slovenian language.