Snuggled in a valley amid the rolling hills of western Slovenia, Idrija strikes many visitors as a charming small town. There are few signs, however, that Idrija was once also one of the most significant towns on the territory of modern-day Slovenia and that its fame extended far and wide.

The story of Idrija’s prosperity began around 1490 when mercury was discovered in the area. The exact details of the discovery have been lost to history, but according to a local legend, a pail maker was washing his products in a nearby creek when he discovered something shiny at the bottom of a pail. The mysterious substance was mercury.

Whatever the veracity of this story, Idrija became a major mercury mining center by the dawn of the 16th century. It soon began to attract miners not just from what is now Slovenia, but also from elsewhere in Central Europe, northern Italy and beyond. A church was built on the spot where the pail maker supposedly made his fateful discovery, and by the 1530s, a grand structure -- Gewerkenegg Castle -- overlooked the town. The castle remains a major landmark to this day.

The production of mercury increased throughout the years, and by the 18th century, more than a thousand miners worked in the mercury pits. The mercury mine – the world’s second largest -- became a major source of revenue for the Austro-Hungarian Empire and eventually produced more than ten percent of the world’s mercury output. More than 700 kilometers of shafts and tunnels were constructed.

The mine brought considerable prosperity to Idrija. Its architecture eventually became increasingly urban in style as Idrija evolved to become of the most important towns in the region. In the 18th century, one of Slovenia’s first theaters opened its doors in Idrija; it remains the oldest surviving theater building in Slovenia.

Education also flourished in the town. A school for miners grew into a technical school – the first in modern-day Slovenia --, and so began a tradition of excellence in education spanned man decades. In 1901, Idrija became the site of the first Slovenian-language high school.

Lacemaking, introduced by the wives of miners from German-speaking lands, also became a vibrant industry. Idrija lace, prized for its intricate designs, was exported throughout Europe and beyond.

The glory days of Idrija’s mercury mining, which lasted for centuries, finally came to an end in the 20th century. Synthetic substances began to replace mercury in most industrial processes, and the demand for the liquid metal eventually began to stagnate. In 1977, authorities decided to close the mine after almost half a millennium of continuous operation.

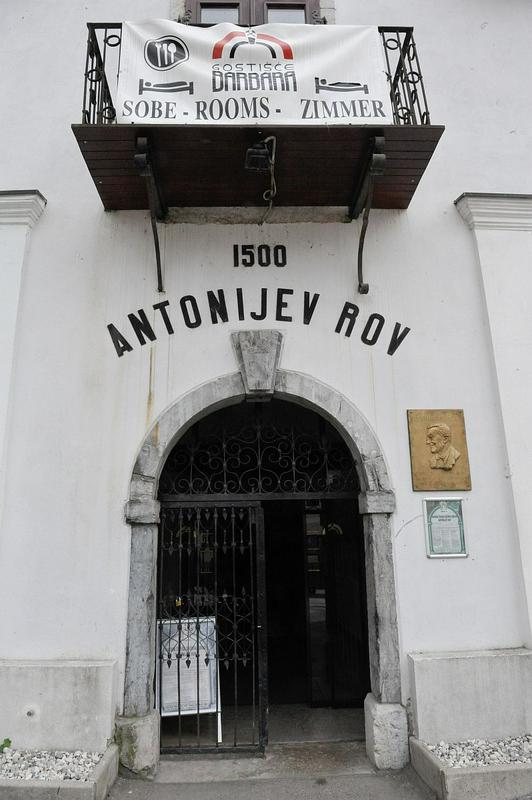

Today, Idrija is counting on tourism to provide a much-needed source of revenue. Visitors can tour a portion of the closed mine and learn about the difficult conditions endured by the mercury miners throughout the centuries. Local tourism got an important boost when UNESCO added the Idrija mine to its World Heritage list in 2012.

Another reminder of Idrija’s past glory exists thousands of miles away. Hidden in a remote corner of California’s San Benito County in California lies New Idria. Now a derelict ghost town, it was once the site of a mercury mine. When it was founded in the 1850s, New Idria was named after one of the greatest mercury mining towns the world has ever known – Slovenia’s Idrija.