The 16th century publication of the first Holy Bible in the Slovenian language was not just a significant development for Christianity in Slovenia; it was also a milestone in the history of the Slovenian language and what would eventually become a distinct Slovenian national identity. The person responsible for the first complete translation of the Bible into Slovenian was an unlikely scholar named Jurij Dalmatin.

Dalmatin was born in the eastern Slovenian town of Krško in the 1540s. The 16th century was the time of the Protestant Reformation in the Slovenian Lands and the young Dalmatin was raised as a Protestant. He was a gifted scholar, and he followed the path of many ambitious Protestants by continuing his studies in Germany, the heartland of the Lutheran movement. There, he studied both theology and philosophy. He also learned ancient Greek and Hebrew. During his studies, he was financially supported by Primož Trubar, a Protestant who had published the first Slovenian-language printed books.

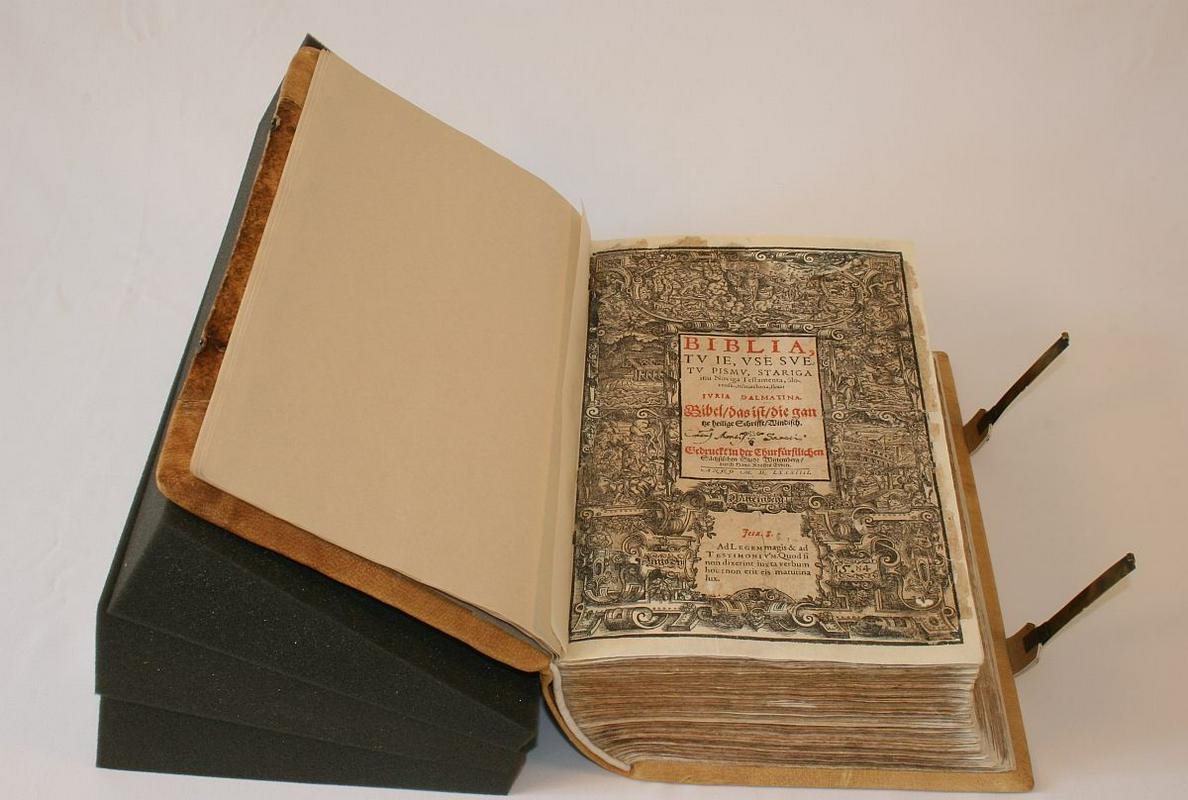

One of the most important new ideas of the Protestants was to bring the Bible closer to ordinary people at a time when the Catholic Church used Latin for its services. Parts of the Bible had been translated into Slovenian before; Trubar, for instance, had published a Slovenian translation of the New Testament, but the entire text of the Holy Bible was only available in German and Latin. Never afraid of an ambitious task, Dalmatin used his linguistic skills to translate the entire Bible into Slovenian. The book, complete with woodcut illustrations, was published in Germany with a print run of 1500 copies. Suddenly, an insignificant peasant tongue had achieved parity with some of the major languages of Europe.

The translation was embraced by Protestant theologians in Slovenia, but predictably, the Catholic Church reacted angrily to its release. It banned its priests from using it, even though many of them continued to use it surreptitiously. During the Counterreformation, the Catholics destroyed many Protestant books, but Dalmatin’s Bible survived – as did its legacy. Eventually, the Catholic Church even formally allowed its priests to use the book. For the first time, the Slovenian people were able to read biblical stories in a language they could understand, an important milestone that led to the emergence of Slovenian as a full-blown literary language.