His name was Valentin Vodnik. He was born in 1758 and eventually decided to devote his life to God. A man of deeply held principles, he rejected the wealth enjoyed by many priests at the time and instead joined the austere Franciscan order. He served in several Slovenian parishes.

Despite his religious commitment, Vodnik’s curiosity extended beyond the Bible. He developed deep ties with several intellectuals who later became known as the leading lights of the Slovenian Enlightenment; he also left the Franciscan order to devote himself to civil matters.

Encouraged by a growing sense of a distinct Slovenian national identity among the elite, Vodnik began to write poetry in the Slovenian language, becoming Slovenia’s first poet in the modern sense. He based his work on folk songs, but his poetry added something new: a sense of irony and satire, often aimed at the authorities.

Vodnik participated in several important firsts. He edited the first Slovenian-language newspaper, became the first journalist in the Slovenian Lands, and even published the first-ever cookbook in the Slovenian language. He eventually became a high school teacher and taught virtually all subjects, from geography to Italian.

In 1809, Napoleon attacked Austria and created the Illyrian Provinces, with Ljubljana as their capital. The French-ruled region stretched from modern-day southern Austria all the way to coastal Montenegro. Significantly for the Slovenian people, the French authorities began to encourage the use of the Slovenian language where only German had once been spoken.

In a widely published political poem, Vodnik embraced the French and their new language policy. He realized that after generations of political suppression, the Slovenian language was on the verge of being transformed from an insignificant peasant tongue into a modern European literary language. Vodnik encouraged the new rulers to expand the role of Slovenian in everything from administration to education. Meanwhile, he continued to write books in Slovenian, including textbooks for the new Slovenian-language schools and grammars for the mass market.

Eventually, the French were defeated and Vodnik, a Francophile, ended up politically and professionally marginalized by the Hapsburgs who retook the Slovenian Lands and remembered his embrace of Napoleon. The pioneering poet and writer died in 1819.

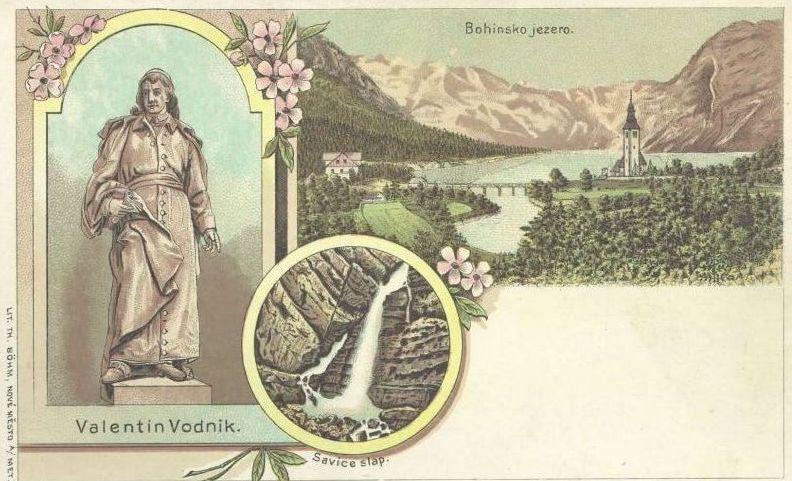

Nowadays, a statue of Vodnik in Ljubljana’s Old Town bears the initials RF, for “République Française” – a reminder of the role the French – and Vodnik – played in the creation of Slovenian national consciousness.