At a time when refugees and their struggle for a better life are dominating newspaper and television coverage around the world, many literature lovers are revisiting the life story of a Slovenian writer who spent much of his youth as an outsider. Now translated into English, Newcomers by Lojze Kovačič feels as relevant as ever, even though it is set in a very different time.

Kovačič was an outsider even when he was born – to a Slovenian father and a German mother, tailors and furriers – in the Swiss town of Basel in 1928. The young Kovačič was sickly and would often miss school. When he did make it to class, he was often dismissed as unintelligent by his teachers.

At the time, the elder Kovačič’s business, which was once a thriving enterprise, began to fail because of accumulated debts. Even worse was to come: As a Slovenian patriot, Kovačič’s father had declined Swiss citizenship, but as World War II approached, Switzerland decided to expel all non-citizens from the country and the family had to leave for Yugoslavia.

They moved to rural Slovenia, where they had problems adapting to a life of farm work, poverty, and sometimes even hunger. Even the Slovenian language was a challenge to members of the Kovačič family, who had spoken primarily German at home, and they were never fully accepted by the conservative local population. The situation didn’t improve even after the family moved to Ljubljana. Tragically, the elder Kovačič died in 1944, and Lojze Kovačič had to provide for the entire family.

After the war, the newly installed Communist authorities decided to deport all ethnic Germans. Most of the family – Lojze Kovačič’s mother, sister, and niece – had to move into a displaced persons’ camp in Austria, but young Lojze was allowed to stay. Eventually, he graduated from the University of Ljubljana, but being half-German and Swiss-born, he had great difficulties finding employment. He was fired from job as editor of a corporate newsletter, and made a living his work making puppetry shows for TV Slovenia. Later, he became a teacher of art, puppetry, and theater.

But it was in his own literary works where Kovačič would leave an indelible mark. His Newcomers (Prišleki) trilogy described his early life as a perennial outsider, a boy who was never accepted in either Switzerland or Slovenia and was viewed with suspicion by adults and his peers. The work includes haunting, deeply though-provoking descriptions of this estrangement as seen through the eyes of a child – in many ways a naïve boy, yet one who was forced to become an adult at an early age.

Even though Slovenian was not Kovačič’s first language and he continued to think in German, his writing is considered some of the best prose ever written in the Slovenian language. Newcomers established Kovačič’s reputation as one of Slovenia’ leading novelists, and he is frequently compared to the likes of Proust and Joyce. Even though the trilogy was his most widely respected work, and has been translated into several languages (including English), Kovačič also wrote other acclaimed novels, including Crystal Time, Childish Things, and Basel, most of them based on his childhood experiences.

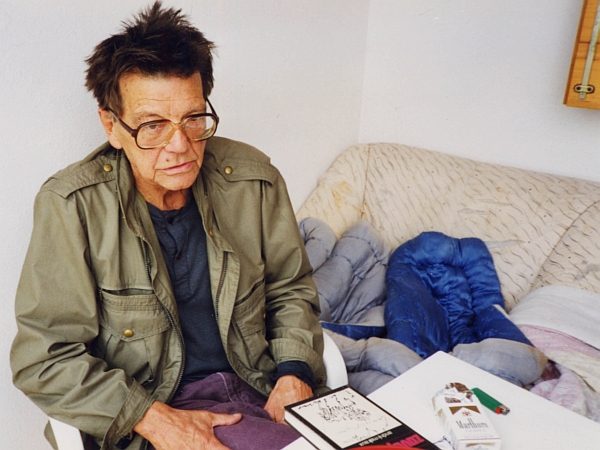

Lojze Kovačič died in Ljubljana in 2004. The eternal outsider was 74 years old.

Jaka Bartolj