"Burek is greasy, ultra greasy, and large," was the title of the article published in the Croatian scientific magazine Etnološka tribuna (Ethnology tribune) in which Mlekuž from the Slovenian Migration Institute (SMI) at the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts tried to clarify the mysterious attraction burek holds for the Slovenian high school students, so much so as to occasionally place it above all the accepted values, in spite of the incomprehension of their own parents, and in contradiction to the national cultural establishment.

It is an interesting question, mainly because it revolves around an oriental cultural element which has been very warmly accepted in Slovenia, a country belonging to the Alpine cultural area. Yet burek (Oriental cake made of pastry dough with filling, e.g. cheese, meat etc.) was brought to Slovenia by the immigrant wave from the formerly shared country. The first consumers were mostly soldiers from the South, but it became so indispensable in Ljubljana that even the Lonely Planet has started recommending "this common, cheap, greasy villain" as a specialty of our capital.

Burek.si

Mlekuž has researched the Ljubljana "burek-subculture" for several years, and he published the book Burek.si?! Koncepti/recepti, (Burek.si?!Concepts/recipes). The field work for the book was done among the Slovenian diaspora in Argentina, among the Slovenian speaking inhabitants of Friuli-Venezia Giulia, and through websites, newspapers, on the Slovenian streets, through high school students slang and in many other ways, wherever he discovered the multi-contextuality and equivocalness of burek.

Jutarnji list doesn't fail to mention that the issue of the comic book "from the other Europe", the one between Albania, Ukraina, Lithuania, and Slovenia, has been titled Stripburek. And that high school burek lovers even paraphrase the verses of France Prešeren’ Water Man to praise it better. Mlekuž has already researched the great presence of burek in the modern culture of Ljubljana high school students, who dedicate songs to it, name the domains after it (burek@mesni) and use phrases as "You can't even afford a burek". And yes, Ali En's ode dedicated to cheese and meat burek is still alive, two whole decades later.

The greasier the better

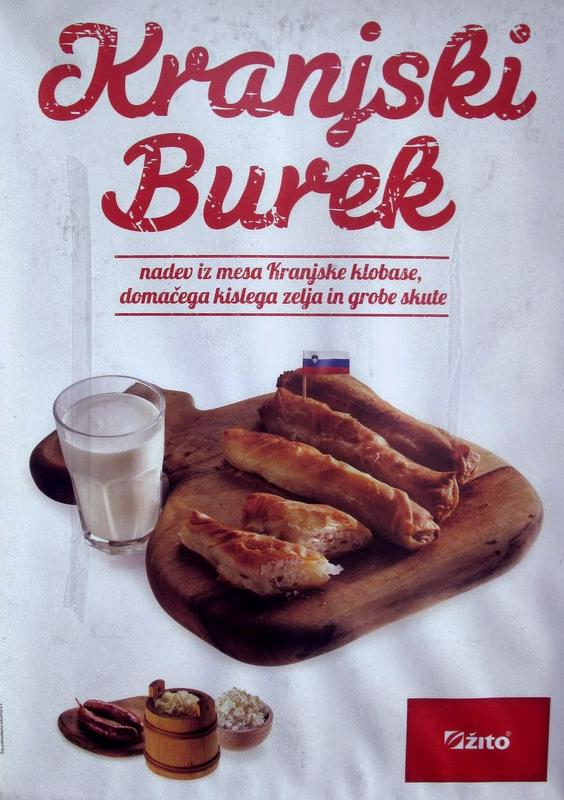

Burek lovers (from Ljubljana) claim the greasiness is burek’s best virtue. The greasier the better. Probably that's one of the reasons that (Slovenian) bureks from Žito or any other Slovenian bakery, which are as a rule dry as dust, never gained popularity compared to those from "the Albanian at the Miklošičeva street" dripping with fat.

Which is of course just the opposite of the publicized healthy life style, considering fat the Achilles heel of burek, thus "triggering pogrom with inquisition and witch hunt", explains Mlekuž.

Yet the young customers are not satisfied with a greasy burek; they look for an ultra-greasy one, and claim that's the »one«. "When you can see burek through the wrapping paper, you know in advance it is good," explains the virtues of a quality burek a pupil of the grammar school Škofijska gimnazija A. J. His peer from the Bežigrad grammar school J. V. says that "burek is greasy by definition". Mlekuž even writes that in one of the shops where burek is sold, close to one of the grammar schools, the "quality" is maintained in such a manner that the employees wash their hands as rarely as possible, believing that in this way burek is always nice and greasy.

Rebellion against Americanisation?

"Without any doubt that is a kind of rebellion against 'Americanisation' and 'McDonaldisation', i.e. antagonism against standardized, rationalized, hegemonic American culture, an escape from the dominant family structure of nutrition and from the authorities of the adults," wrote Mlekuž. Simultaneously it is also a form of objection against yugo-phobia, balkano-phobia, and other nationalistic phenomena, which can be noticed from discussions, comments and statements at a number of websites and forums, and in graffiti as for example "Yes to burek, no to mosque??«.

This was also the topic of the diploma work The meanings of burek in Slovenia (2010) by Bojana Rudovič Žvanut.

But the entire debate is, according to Mlekuž, only an appendage to the pompous style of cultural communication, attracting attention by stirring, switching, and disrupting the dominant meanings. »The rebelliousness« of young burekophiles should thus be most likely put in quotation marks, and the reason for appropriation of burek by high school students probably results from availability (open 24 hours per day), satiability, low price and popularity of burek. The discussions on healthy life style and rebellion against come afterwards, and only add spice to burekmania, concludes Mlekuž.

"We should protect it before the Slovenians do"

Perhaps for us the comments below the article are even more interesting than the article itself, which was published by both Croatian and Serbian media. "Our approach should be that, considering most of the young Slovenians have Bosnian roots, it is no wonder that burek is so popular," was one of the comments. There were quite a few similar ones: "It is understandable Slovenian highs school students like burek – they are all Bosnians!"

The other group of comments leads into another direction. "Now also burek will become Slovenian property, ha-ha." And: "Let's protect burek before the Slovenians do! Hurry!"

The direction Žito has taken with their Carniolan burek with cabbage, cottage cheese and pieces of Carniolan sausage, and with a little Slovenian flag stuck in it, is dangerously pointing into that direction …

K. S., translated by G. K.