The horrors of the Nazi concentration camps inspired some memorable art and literature. Systematically deprived of human dignity, camp inmates often seized every opportunity to express their creativity in the midst of unbearable conditions. A Slovenian painter and architect left a permanent record of the suffering in an unlikely medium.

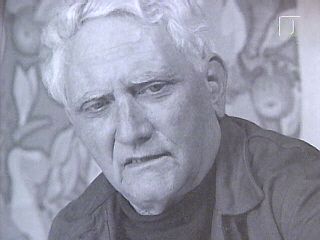

Born in Ljubljana in 1905, Boris Kobe was a talented Slovenian painter and architect. Before the war, he studied under and later worked with the famed Slovenian architect Jože Plečnik, and among other projects, he designed a pond and a playground in Ljubljana’s Tivoli Park.

When Ljubljana found itself under Axis occupation during World War II, Kobe was arrested as a political prisoner and was sent to Allach near Munich, a subsidiary of the infamous Dachau concentration camp.

Kobe managed to survive his imprisonment. In the days after the camp was liberated by American troops, and Kobe was waiting to be transported home, he left a record of the horrors of the camp -- in the form of intricately drawn tarot cards. Made to enable the survivors to socialize with each other, the cards featured scenes of torture, humiliation, pain, and suffering, but all leavened with a kind of dark humor that had helped the inmates to survive the hellish conditions of the camp.

The cards also contained some glimpses of hope: One of them portrayed U.S. forces liberating the camp, while another showed the Slovenian flag proudly announcing the end of fascist rule.

After the war, Kobe went on to work on a number of paintings and architectural projects. He helped to restore Ljubljana’s Old Town and became one of the leading designers of monuments. In 1977, four years before his death, Kobe received Slovenia’s prestigious Prešeren prize.

The cards, meanwhile, remain among the most prized collections of Slovenia’s National Archives. Their reproductions have been on tour around the world, including at such venues as the 2000 Stockholm International Forum Conference on the Holocaust. Even though they were made almost 70 years ago, the cards serve as an all-to-relevant reminder of man’s inhumanity towards fellow man, as well as the power of humankind’s drive to survive -- and to create.