Žiga (or Sigmund) Zois was a Slovenian industrialist; among others things, he operated several ironworks. But he was much more than that. As was common at the time, he used his wealth to serve as patron of the arts, a man of books, and a collector of minerals.

Zois was born in the port city of Trieste in 1747 to a nobleman father from modern-day Italy and a mother from the Slovenian region of Upper Carniola. After spending some time studying in Italy, Zois came to the Slovenian Lands and, at the age of 27, took over the family’s business – primarily in trade and the ownership of ironworks and mines.

But Zois’s interests went far beyond business. He was a man of the enlightenment and saw education as a key to progress; he developed a strong interest in the natural sciences and worked closely with Belsazar Hacquet, a French-born researcher based in Ljubljana.

He was just as determined to be an influential patron of the arts. He hosted the most prominent intellectuals of the day in his mansion. A passionate believer of language as the cornerstone of national identity, he inspired Valentin Vodnik to became the first Slovenian poet, and convinced Anton Tomaž Linhart to begin writing in Slovenian. Also under his stewardship, Jernej Kopitar published the first Slovenian grammar. Zois’s work was not only important for science, but was also crucial for the emergence of a Slovenian national identity after centuries of German domination. His championing of the Slovenian language had its limits, however: His own literary output failed to receive much praise, and he ultimately came to doubt the language’s artistic potential.

Over the years, Zois also established an impressive collection of minerals, which is now one of the main attractions of the Slovenian National Museum. He was also a passionate ornithologist and kept invaluable records of Slovenian names for various bird species.

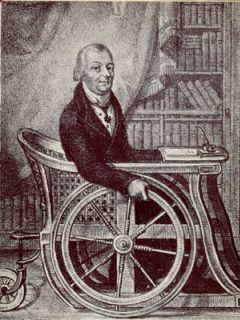

Once the richest person in the Slovenian Lands, Zois lost much of his fortune after much of modern-day Slovenia became a French province in 1809. Within a few years, his gout made him unable to walk. He died in 1819, aged 71, but his legacy lives on.

At a time when many Slovenian industrialists seem interested only in turning a quick profit, Žiga Zois is remembered for his determination to elevate the Slovenian language to a new status and give the Slovenian people a sense of pride in their culture.

Jaka Bartolj