My two sons. This is what is really important to me. Theatre is good. That’s what I do. But when it comes to taking decisions, I always take decisions that are best for my little boy.

He has worked in almost all the major Slovenian theatre companies, but most of time he was at Ljubljana Drama and Slovensko mladinsko gledališče.

If we consider only the roles for which you have received awards, the variety is impressive, from Puba Fabrici in Gospoda Glembajevi (The Glembaj Family) by Krleža, Georgij in Osvoboditev Skopja (Liberation of Skopje) by Jovanovič, the legendary Scapin in Les Fourberies de Scapin (Scapin’s Deceits) to the sophisticated, playful Mediterranean characters in Dario Fo's works. How do you nourish this variety? Is there a formula?

I would not know. There is no formula. That is your nature. For an actor, it is necessary to preserve the child in oneself, to continue to play. If you lose this and you say, “I'm through, this is not a serious profession”, it means that your fire has gone out and you are only good for sitting on the pier and fish (laughs). But I think that all actors have the desire to act. As the years pass the memory is not as quick as before, but the desire never fades.

You were also a professor at the Academy of Theatre, Radio, Film and Television (AGRFT); what is, in you opinion, the major difficulty in the forming of a young actor?

I noticed that there were very few students who did not have any problems. Each of them came to the academy with a suitcase full of frustrations, and until this is overcome, it is difficult. I kept telling them that on stage they can do whatever they like, all the things that they would never do in real life. That the stage is the only place where they can really open up. But it takes some time before they understand it. They hide; they are embarrassed to show their feelings. But, when this phase is over, some already show their potential as students, some open up later, and some never, unfortunately.

Some actors are pursued by their roles. Has this also been your experience?

No, thank God. The only case that comes to my mind, we taught it also at the Academy, was the case of a Russian actor who played Lenin and identified with the role to such an extent that he was unable to return to his normal life. He finally went mad and ended in an asylum. You must not allow this. When the performance is over, you must step from that universe into the real world. That’s that.

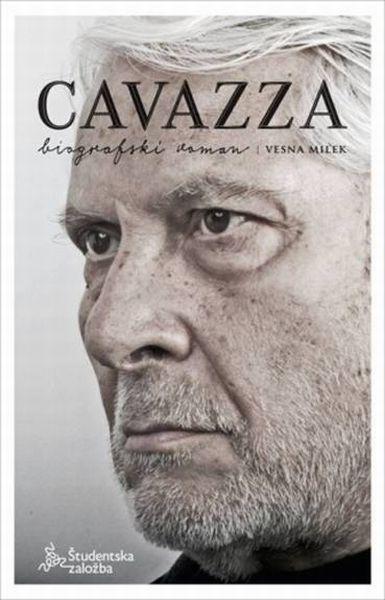

A book on your life, written by Vesna Milek, was published by Študentska založba in 2011. Pain is a recurrent feature in this book. You speak, for instance, of the “the feeling of being constantly alone, alone with your own s..t and your humiliation”. What do you mean by that? How do you fight against injustice?

Against injustice? It is difficult, almost impossible. When you experience an injustice, you are really alone. People around you may comfort you, but if the injustice is profound, it stays with you; it cannot be erased. I am not a vindictive person. At the beginning of my career, some colleagues were not very helpful, to put it mildly, and this marked me for life. I never stopped associating with them, though, I really do not bear a grudge against anybody.

In the 70s and 80 you acted mostly in so-called political theatre, where roles were clearly defined. How do you now view this period? Do you have the impression that, with certain young directors, political theatre is coming back?

The atmosphere then was unique. In Ljubiša Ristić’s day, we performed only political pieces, and everybody knew why. This was a way to fight the establishment; it was popular to be a dissident. Today, I do not see the sense of such committed theatre. Challenging what? Globalisation? That’s boring. Although pieces like that are already being written, about characters being sacked after thirty years of work with a letter waiting on their desk. You open the letter and see that you are not wanted any more: please pack your bags and leave. These are topical issues today.

There is a lot of talk about absence of values. Considering that values have always been the basis for dramatic creation, what do you think might replace these values, so that we may still see interesting presentations?

With younger directors, I now have the impression that they tend to overturn everything, so it is sometimes difficult to comprehend what values the piece is about. And in the various committees, there are people who somewhat support this attitude by giving awards to these directors. But the ordinary theatre-goer hates this. For us, this hermetic attitude has no meaning. I sometimes do not even understand the plot. But I think that theatre will rise again, as there are people who think and understand the importance of the actor and the text. Who do not tear up the text, write their own lines, and turn everything upside down. For example, what attracts audiences to Ljubljana's Drama? Mala Drama has the most popular programme; it stages pieces in which the texts can hardly be ‘reinvented’, which are about people, about relationships. While works presented on the big stage are usually ‘full of creative ardour’ and often make no sense at all.

In a way, capitalism has become the ‘must’ of comedy in theatre, particularly commercial productions? What is your view? Is it possible for an honest actor to express himself in such productions?

I participated in two commercial productions. The first was Balkanski špijon (The Balkan Spy), which actually is not a commercial text, and I insisted that the piece be played as a serious comedy. This is why it was such an enormous success. The second was 5 moških.com (5 Men.com) in which I participated at the instigation of Jurij Zrnec. But in fact, I quite rapidly got fed up. So I left the project. I personally do not watch these shows. The problem with commercial projects is that actors, by themselves, are not important; the performers are often people who are currently popular and for this reason, are included in the show. In such cases, also the audiences have never been to a theatre before.

You have also had an outstanding directing career. In your opinion, what is the difference between acting and directing, in terms of self-fulfilment? If there is one, of course.

I started to direct at the Academy, as in one academic year no student of directing was admitted and I was the only teacher without an aspiring director in his class. And then you say, why not do this for living? Directing is a wonderful experience. As an actor you only care about yourself and somewhat neglect others, but as a director you have to have control of everything. This is a very creative profession. And besides, it's perfect, because afterwards, you don’t need to act. You do your directing and leave, while they continue to work hard (laughs).

What is most important for you now?

My two sons. This is what is really important to me. Theatre is good. That’s what I do. But when it comes to taking decisions, I always take decisions that are best for my little boy.

Vesna Žarkovič, SINFO

My two sons. This is what is really important to me. Theatre is good. That’s what I do. But when it comes to taking decisions, I always take decisions that are best for my little boy.