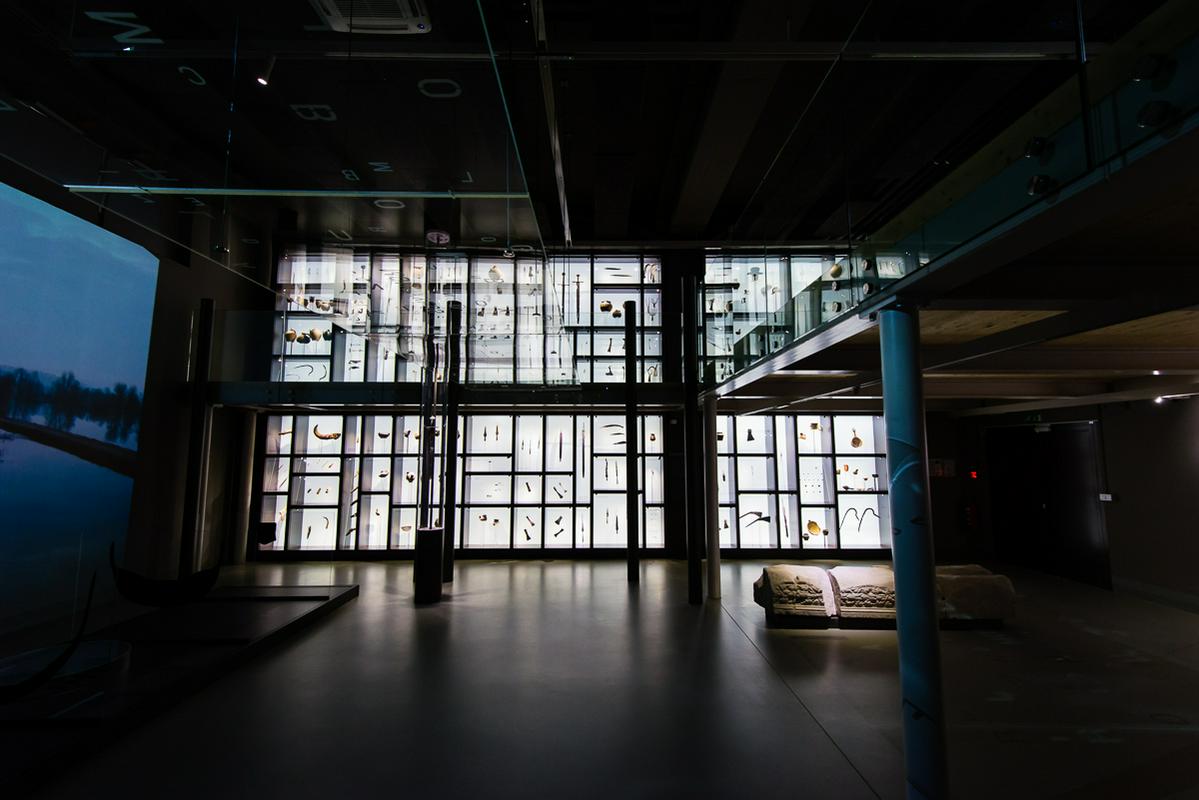

At first it was the grand size of the ancient vessel that grabbed all the attention. In Europe today it mostly stands out because of its exceptional quality. The remarkable find has brought archeologists a number of surprises; especially interesting is the realization that it is much older than first thought.

An initial analysis said the dugout canoe could be dated back to the 1st century AD (in 2001 and 2008 archeologists sampled parts of the dugout exposed to water currents, plants and animals, which can contaminate an object with carbon.). However, more recent and more reliable data shows the dugout was in fact built in the second part of the 2nd century BC. "It doesn’t mean, that the initial idea of it being a Roman dugout should be ruled out. Such a dugout, together with all the effort put into its maintenance, point to the direction that it was used by many generations. We now call it a Celtic-Roman dugout, and I think it will remain at that," says archeologist Andrej Gaspari, PhD. The dugout canoe (Deblak) was made out of a single oak tree, which started growing in the 4th century BC. Two hundred years later it was cut down for making the dugout. It must have been a very nice and tall tree with a diameter of 1,5 meters. More about the tree itself, and especially about its natural habitat, will be revealed by experts from the Biotechnical Faculty.

Dugouts from the Roman period are not surprising to archeologists. Such an elegant vessel could easily be compared with other vessels from that time which tell about the lively local transport route between the ancient cities of Navport (Vrhnika) and Emona (Ljubljana). However, the new dating which traces it back to the 2nd century BC, has turned things topsy-turvy.

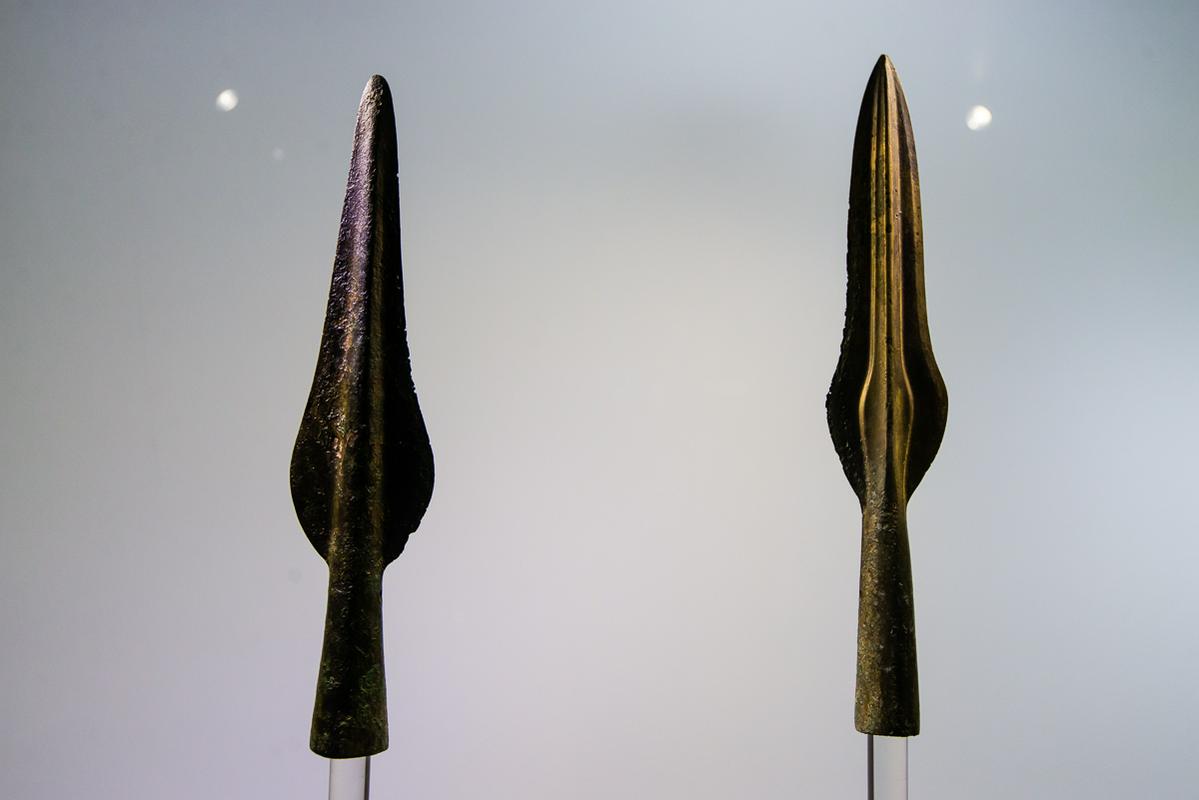

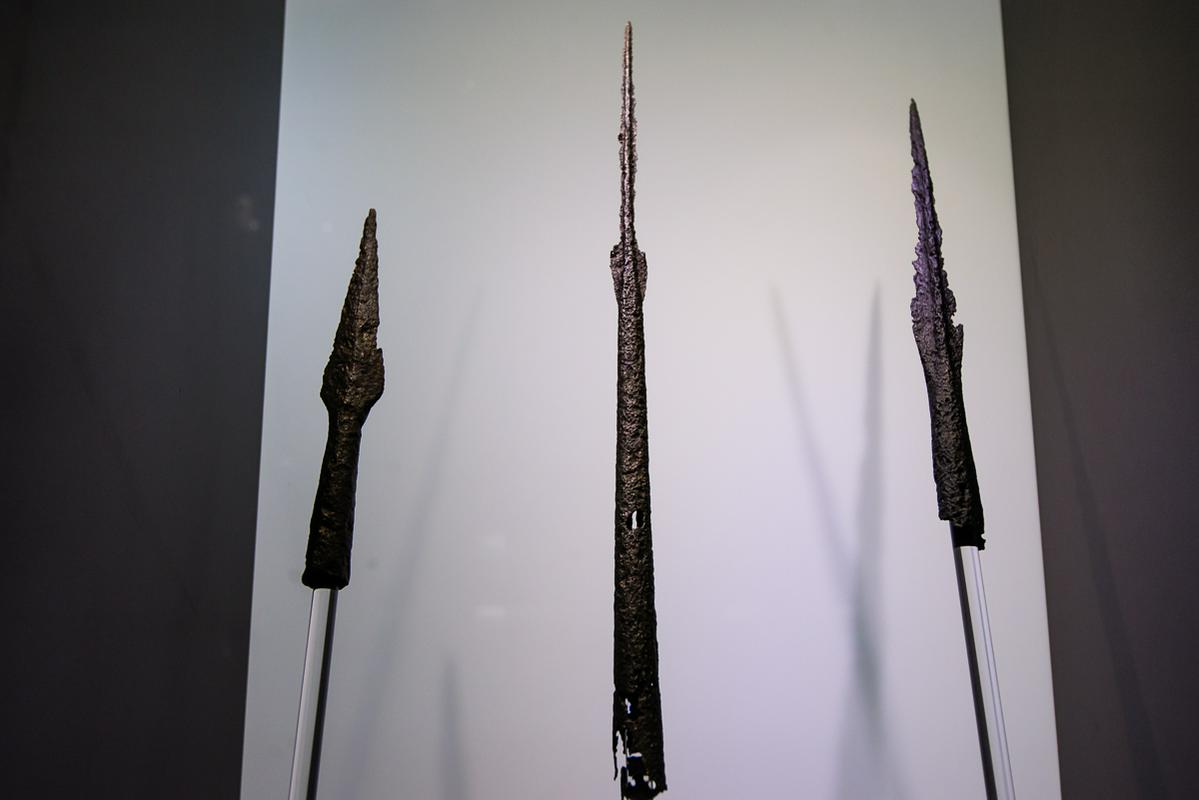

The region in question was different and much gloomier in the 2nd century BC. The area was populated by an entirely independent tribe union, which was dominated by the Celtic Taurisci tribe, which also settled most of the eastern Alpine region. Excavations from preserved Celtic graves show that the Taurisci economy was war-oriented. Their economic power relied on the supervision and trade control of the Northern Adriatic with the central Danube region, especially the trading of slaves captured from inter-tribal wars in late Republic Rome. The slaves were later traded for serving armies in the Northern Albanian and Black Sea principalities. The Taurisci did not show much interest for the more profitable business of gold digging in the High Tauern range, explains Gaspari. In the 2nd century BC the Taurisci tribe showed aspirations for Venetian land, which the Romans then protected in the year 181 BC with the establishment of the ancient city of Aquileia. Their allies, the Venetians, made the establishment of the Roman city possible because of increasing pressure from the Tauriscis, who had started settling the originally Venetian territory. The aim of the Tauriscis was to assume control on both sides of the Ilyrian-Italic gates, in order to ensure income from taxes and other such sources.