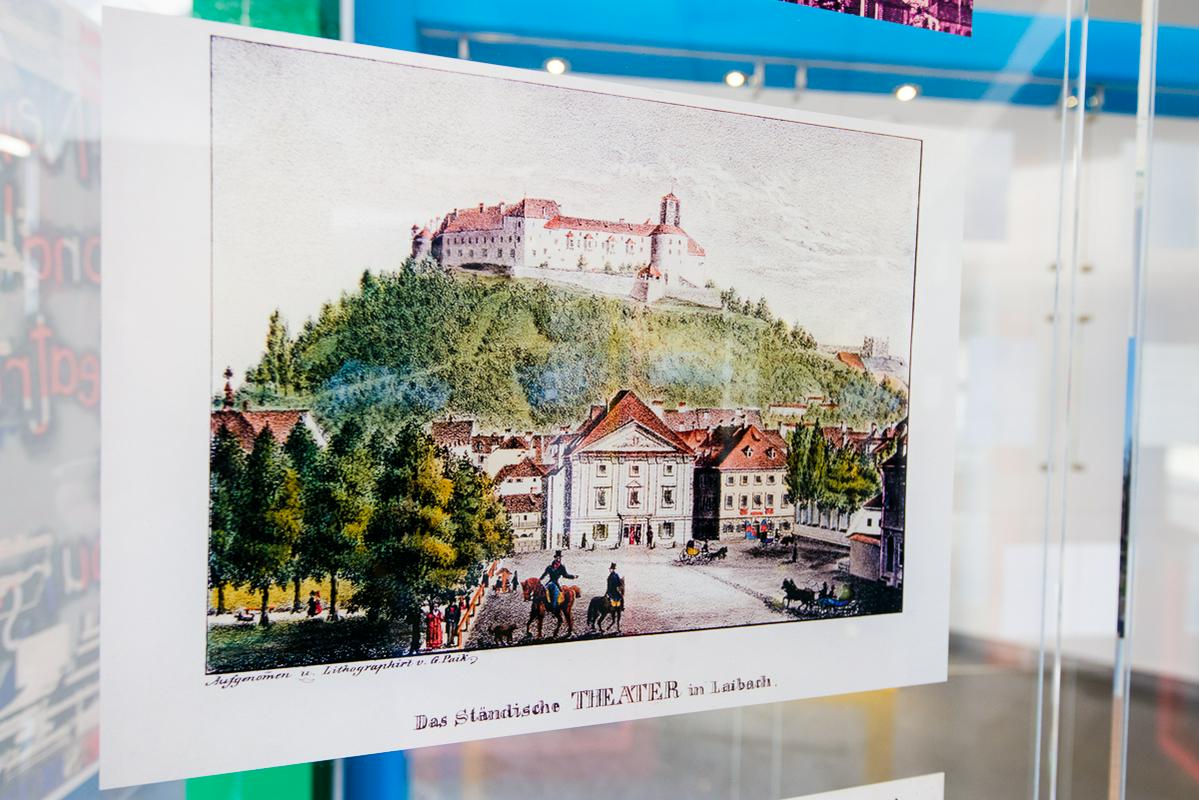

One of the main drivers for the establishment of the Dramatic Society was a desire among Slovenian intellectuals in the late 19th century for Slovenians to have their own theatre. The earlier history of the theatre in this country also contributed to this end, from Trubar's dialogues between father and son in his book Abecednik (Abecedarium), to the Jesuit and Capuchin theatre productions, as well as Linhart and Drabosnjak, visiting Innsbruck comedians and Italian operistas, and more than 100 years of the German Theatre (founded in Slovenia in 1765).

Anton Tomaž Linhart is a notable pioneer of modern Slovenian theatre, and someone whose work led to the founding of the Dramatic Society. Moreover, the general tenor of the age in the so-called Spring of Nations, the wave of political upheavals that occurred throughout Europe in 1848, raised awareness of the need for a truly Slovenian national theatre. The beginnings of the Dramatic Society thus date back to the Age of Metternich and Bach's absolutism (1848–1851), and include activities by the Slovenian Society in Ljubljana (1848–1851) and the Leopold Kordež Theatre Society (1850–1850), and the Ljubljana National Reading Room (1861-1867).

The foundation of the Dramatic Society was further aided by the success of young patriots still working at the reading room stage, and the first meeting of the Society was held on 24 April 1867. The attendees realised that theatre had to go beyond reading rooms, and could not serve as an amusement, cultural institution and stage for declaring patriotic slogans all at the same time. The committee of the newly-founded Society, which comprised twelve members, elected Luka Svetec as president, Peter Grasselli as vice president and Josip Nolli as secretary. The ambitious founding project was reflected in the rules of the Dramatic Society, which were drawn up by Josip Stare and further elaborated on by Stare, Grasselli and Nolli.

Not just a slightly better amusement

When Fran Levstik became president of the Dramatic Society in 1868, he introduced amendments to the rules in order to encourage the emergence of original Slovenian drama. From today's perspective he made an especially important contribution, since he relentlessly pursued the idea of a Slovenian theatre which would not only operate as a "slightly better amusement," but also be a high temple of art that, as he wrote, "aesthetic judges [will] name the most beautiful flower of all poetry on Earth". He was one of the few people with a large-scale vision of the future of Slovenian theatre, although unfortunately this could not be realized in political, cultural and social context of the 1860s.

One of the Society's priorities was the theatre school, which was founded in 1869 and, with minor interruptions, remained open for fifty years. Although it was not able to prepare most actors to become professionals immediately on leaving, it taught the basics of theatrical gestures and rhetoric, so its students were able to perform on stage, and for this alone it is very important. Moreover, the managers of the Dramatic Society were aware that teachers in the school could not rely on practical knowledge, but also needed a theoretical background. For this reason, the Society published a work entitled Priročna knjiga za glediške diletante (A Handbook for Theatre Laymen) in 1868, which was the first such text in Slovenia. Another achievement was Slovenska Talija, a collection of translated and original plays, which was first published in 1867. With this, the Society acquired a library from which it was possible to create a repertoire which eventually grew to 120 books. This is another of the Society's most significant achievements.

Finally, an art theatre was gaining ground

When the greatest Slovenian actor of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Ignacij Borštnik (1778–1882), stepped on stage in 1882, it symbolically marked the beginning of a true art theatre in Slovenia. However, it was in January 1885, when Borštnik played the main role in Nestroy's He Will Go on a Spree (Einen Jux will er sich machen), that the public truly recognised his enormous talent. In 1894, Borštnik moved on to perform at a larger theatre in Zagreb, and left behind a considerable void in the Slovenian scene, which was then dominated by Czech actors. Besides Borštnik, there were many other individuals who also contributed to the establishment of Slovenian theatre. Josip Nolli was among the group of actors who were took part in the Dramatic Society from its earliest days. Up until 1875, he worked as an organiser, actor, singer, translator and author of original plays. After his international career as a baritone singer took off (1875–1890), he worked to improve the opera performances at the Provincial Theatre, where he worked as a director. Fran Gerbič contributed to the establishment of musical theatre in the country, returning to Ljubljana in 1886 after building a successful European career as a dramatic tenor and becoming, among other things, a conductor at the Dramatic Society. Others who pushed the boundaries of theatre at the time include Zofija Borštnik Zvonarjeva, Anton Verovšek, Avgusta Danilova, Anton Cerar Danilo, Hinko Nučič and Milan Skrbinšek. Anton Trstenjak was also working as an organiser and teacher at the drama school in these years, as well as being a theatrologist, while Ivan Cankar was working as a playwright, and Fran Govekar, Friderik Juvančič and Hinko Nučič as intendants. After Borštnik moved to Zagreb, the Czechs who left the deepest impressions on the local scene included the actor, director and intendant Rudolf Inemann, actor Rudolf Deyl, and conductor Hilarij Benišek.

The development of a Slovenian repertoire was another significant development. While long-based on trivial dramas, farces, comedies and singspiel, after the Society began performing in the newly built Provincial Theatre in 1892 (today's Slovenian National Opera and Ballet Theatre), the repertoire was enriched with the addition of many plays and operas from abroad.

Initially, the Dramatic Society shared space in the new theatre with the German Theatre, but gradually became more prominent. After the Germans grew uncomfortable with this arrangement they built their own establishment in 1911, the Franz Josef Jubilee Theatre, which is now the Slovene National Theatre Drama in Ljubljana. In 1919, after the Germans left, the building was also open for Slovenian theatre.

In 1900, the preeminent Slovenian playwright Ivan Cankar began his theatrical journey, although his plays were too advanced for the time and clashed with the expectations of the audience. As such, his works were not very popular at first, but became more widely accepted after World War I.

During the Great Depression, from 1914 to 1918, the theatre remained closed for four years and a cinema was set up in its building, but as the economy improved Slovenian theatre was reborn. The theatre was then nationalised in 1920, and in the new country – the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, it became a systematically financed cultural institution, and the nation's symbol of its cultural maturity.